By Jean Asselin

Abstract

This article presents a theme-based curriculum for the teaching SF literature. Sets of 15 stories each, six in all, match the number of weeks in the North American semester system. Selection criteria include theme, awards won or nominated for, and critical recognition. Curricular material is taken from 80 years of published SF, presenting the genre through accessible stories that nullify the requirement for prior knowledge of SF literature. A third of the stories were adapted for the screen, which provides the opportunity to lure students by referring to media they know well, also to demonstrate the greater depth associated with the written story. Three quarters of the texts in this curriculum are currently available online, most of them individually, a proportion expected to rise as publishers transition to digital media. The resulting flexibility allows for the curriculum to be revised at will, and extended to subjects other than English. Brief thematic summaries of each of the 90 stories are provided, and stories are mapped to U.S. Common Core State Standards for grades 6 to 12.

INTRODUCTION

Science fiction (SF) is defined by Barthell (1971) as a literature of ideas, a definition refined by Gunn (2005) as a literature of change, since new ideas entail consequences. The nature of these changes are therefore central to SF, yet the latter’s themes are seldom used systematically to present the field to new readers.

In order for SF to empower the citizenry to think about the world they want, the full scope of the genre must be taught, and the continuity and relevance of its themes addressed. This article presents a theme-based curriculum for the teaching SF literature.

This curriculum fills the gap between existing types of anthologies. Yearly “best of” series (see Dozois, 2012; Strahan, 2013) purposely avoid theme. Single-topic anthologies (Kelly & Kessel, 2012; Adams, 2008, 2009, 2011), while they suggest some thematic coverage, do not relate one topic to another. Larger anthologies designed as textbooks do not address theme directly (for instance Gunn, 2002), or treat it as an undeveloped afterthought annexed to the back of the volume (as in Evans et al., 2010).

As of this writing, no SF anthology can be assembled from texts available online one by one, an omission this paper wishes to correct, as the resulting flexibility means a curriculum that can be revised at will, and even extended to subjects other than English.

As a genre, SF values originality, with newly published stories that build upon the old, and develop the tropes over time. This makes contemporary SF daunting to new readers who, in effect, always comes late to the game. Consequently, curricular material is chosen all over some 80 years of SF corpus build-up, presenting the genre through accessible stories that nullify the requirement for prior knowledge of SF literature.

In addition, the curriculum comprises a range of stories that challenge the perception of science fiction as juvenile genre, and aims to appeal to readers not attracted to SF in the first place, in the spirit of the long out-of-print anthology “Science Fiction for People Who Hate Science Fiction” (Carr, 1966.)

As pointed out by Gunn (2006), what is shown on television only looks like science fiction. While some take delight in a more widespread SF-like attitude towards the world (Csicsery-Ronay, 2008), others lament that “Sci-Fi”, as audiovisual media SF is often referred to, increasingly defines SF to the public at large (Stableford, 1996), diluting its concepts and relevance in the process.

Finally, stories listed herein map to Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science and Technical Subjects. Theme-based curricula map readily to educational standards, unlike other descriptors of SF such as subgenres or literary criticism.

METHODOLOGY

This curriculum is modular, focuses on themes, combines multiple story selection criteria, addresses specific curricular needs, and is independent from the limitations inherent to printed formats, such as fixed story sets, or much delayed newer editions.

Modularity

The curriculum is subdivided in sets of 15 stories each, a total that matches the number of weeks in the semester system. The modular design gives teachers the flexibility to choose between any multiple of 15 stories, up to a theoretical maximum of 90 using all six modules. Using half a set—7 or 8 stories—is possible should the teacher decide that exploring a smaller number in greater depth is warranted, or that students are not ready for more. The overarching curricular goal of each module is as follows.

Introductory. This is a scale model of the entire curriculum, with each of the selection criteria (detailed below) reflected in a single module. The 15 stories are ordered so that the reader unfamiliar with—even reluctant about—science fiction will quickly discover stories, which concern the human condition a hook generally associated with non-genre stories. This module is the preferred entry point.

Emphasis A—Women writers. The stories in the second module are written solely by women, some who would consider themselves feminist, others not. Without this module, the overall curriculum would inadvertently reflect a past where women writers were underrepresented. This module celebrates a view of SF particular to half of humanity, one which is essential to the long-term survival of the genre.

Emphasis B—Adaptations for the screen. The stories in the third module were adapted for cinema or television, five of them as big budget movies. Audiovisual media exerts a vast influence on the public’s taste for SF while often watering down its concepts. This module illustrates the advantages of SF in literature over visual media, and why students should read it. Along with the twelve adapted stories distributed elsewhere in the curriculum, these texts can be used to hook the students to literature by means of the TV and cinema productions they already recognize.

Emphasis C—Timeline of the SF genre. The last three modules reflect the evolution of SF since its appearance as a distinct genre in 1926. For the purposes of this curriculum, three periods will be defined as Classic (1926-1965), Transitional (1966-1985), and Modern (1986-2005), with one module per time period. While the above subdivisions are by no means universally accepted, they can be justified as follows.

Classic. This is the developmental era of SF, from its pulp magazine beginnings as a specialized genre to an awakening that SF can and should be true literature, and the founding of its professional writers association.

Transitional. This interval begins with the coining of “New Wave SF” (as cited in Wolfe, 2005, p. 19), and ends with the triumph of Neuromancer, the flagship novel of cyberpunk, a major subgenre that emerged in the early eighties.

Modern. This last period encompasses conflicting trends such as the polarization of hardcore cyberpunk versus mainstream-leaning authors (Swanwick, 2005), and a simultaneous UK renaissance of the space opera subgenre. The module purposely ends in 2005 in order to allow for the selection of stories that stand out over time. However the modularity of the online curriculum allows this selection to move forward as later works become more influential.

Thematic content

The curriculum uses the Human Evolution Framework proposed by Asselin (2012), where it is argued that the changes addressed by SF are future projections of concerns rooted in our evolutionary past: the tools we use (stone implements in the past; robots in the future), the settings we explore (the next valley; the next planet), others we meet (other tribes; otherworldly aliens), invisible dimensions we think about (divining the future; travelling there), how to master them and the world by changing our essence (shamans and the supernatural; mutants and superpowers), the rules that organize our societies (loose-knit hunter-gatherers; finely structured utopias), and the habitat we transform (waste accumulation within village walls; radioactive wastelands). Themes are thus classified in seven broadly defined categories:

Machine Intelligence. Intelligent tools, and their interface with humans.

Space Faring. Humanity traveling and living in the cosmos.

Extraterrestrials. Non-human intelligent life evolved on other worlds.

Inter-dimensional. Different spacetimes such as time travel or alternate realities.

Trans-human. Humans modified by mental powers or physical alteration.

Newtopia. Society structured via new rules or constructs (continuity is implied).

Devastation. Wastelands/survivors, post-cataclysm or not (rupture is implied).

Every module comprises two stories for each theme category. The fifteenth story is a “wildcard” that completes the thrust of each module with extra selection flexibility. The focus on theme brings automatic emphasis on those seldom treated in other media such as human transcendence, new models of societies, and life in a truly devastated world. It underlines the potential of other themes to exceed the scope of the all too frequent murderous robots, spacecraft as airplanes, monstrous aliens, and zero-consequence time travel.

Selection criteria

The selection criteria include awards, critical recognition, story length, humor, and online availability.

Awards. Most of the 90 stories were nominated for one of the major SF annual literary prizes, colloquially known as the Hugos and Nebulas, that have rewarded excellence since 1953 and 1966 respectively. Many appeared in all-time best SF lists, either the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies (Silverberg, 1970; Bova, 1973a, b) gathered to recognize the best “pre-Nebula” stories, or the poll run by Locus Magazine in 1999, part of which is used here as a “pre-Hugo” equivalent. The overall average is one nod per story. In order to make the author selection less arbitrary, a tally of award wins and nominations was made, with the highest scoring authors given extra weight.

Critical recognition. Thirty stories in this curriculum appear in “The Road to Science Fiction” (Gunn 2002), and fourteen in “The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction” (Evans et al., 2010); nine stories, all in the Women writers module, appear in “Women of Wonder” series (Sargent 1975; 1976; 1978; 1995a, b.) All but two stories were translated for the francophone market, twenty-four alone for the multi-volume “Grande anthologie de la science-fiction” (Klein et al., 1974; 1983); nearly a third of the authors herein appeared in the author “best-of” series “Le Livre d’Or de la science-fiction” (Goimard, 1978), later expanded as “Le Grand Temple de la S-F” (Goimard, 1988.)

An alternate, compiled approach to critical recognition is provided by Harris (2010), who derives classic SF volumes by tabulating titles from critical SF reading lists (for instance Barron, 2004; Gunn, 1977; Hartwell, 1996; James, 1994) and reader polls. The method yields mostly novels and, unlike awards, favours older titles listed anew, yet the resulting author list shows a significant overlap with this curriculum.

Length. Short fiction introduces SF themes while keeping a reasonable limit on reading time commitment. Using the standard Hugo and Nebula categories for fiction length, this curriculum is composed of 45 short stories, 33 novelettes, and 6 novellas. Novels being an important part of the genre, with additional requirements in world-building, depth of characterization, and plotting, each of the six sets includes one novel excerpt, of novelette length, as incentive to seek more. Teachers who wish to use novels only may seek Booker and Thomas (2011), who emphasize subgenre rather than theme.

Humor. While humor is not readily associated with SF, many authors use it to great effect. Each module includes at least one story that is humorous, namely texts from Spinrad, Emshwiller, Sheckley, Vonnegut, Lafferty, and Cadigan.

Curricular needs

The requirement to raise reading skills at every level of the educational system calls for stimulating student interest. The strong presence of SF in popular culture as a distinct genre can be leveraged to lure students to read.

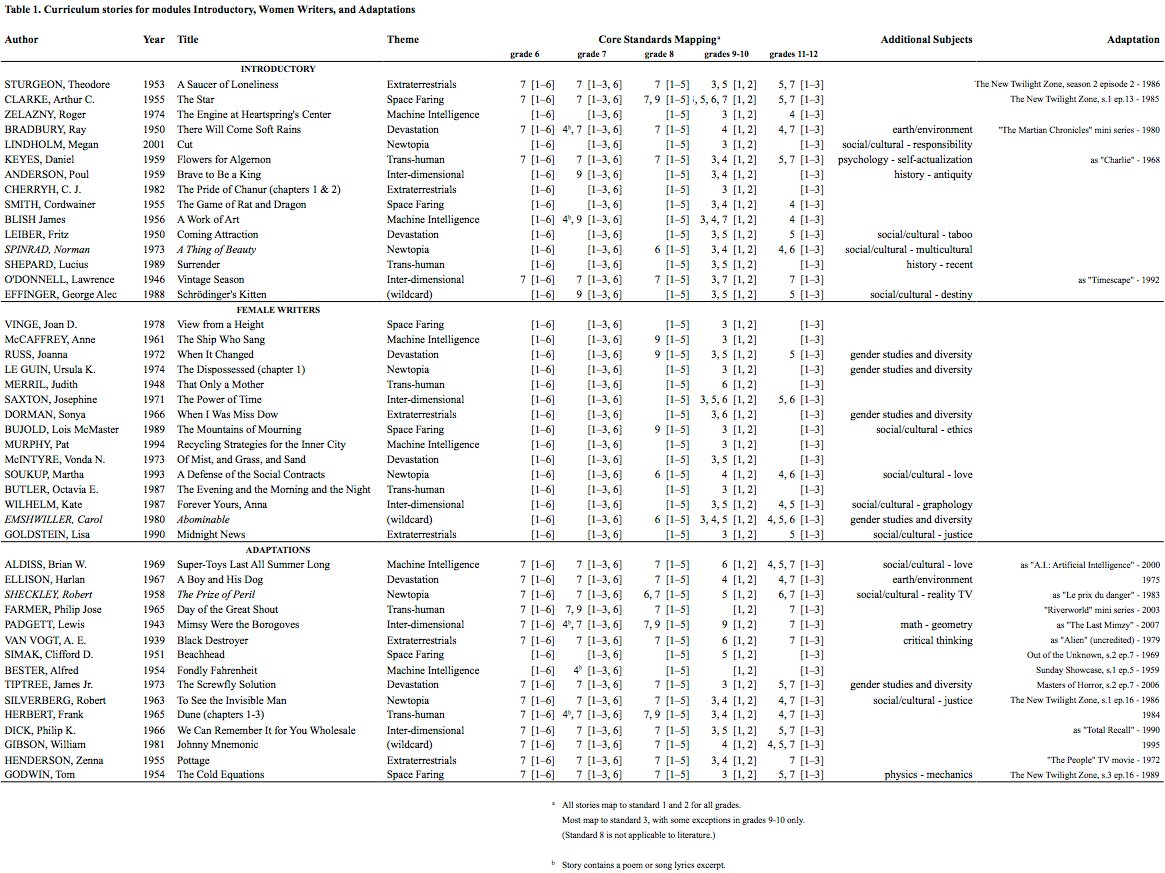

On March 19, 2013, a bill was introduced in the West Virginia Legislature (2013) “requiring inclusion of science fiction reading material in certain existing middle school and high school courses to stimulate interest in the fields of math and science.” http://www.legis.state.wv.us/Bill_Status/bills_text.cfm?billdoc=hb2983%20intr.htm&yr=2013&sesstype=RS&i=2983 The present modular virtual anthology would allow teachers to comply with such a bill without being required to hold a degree in SF literature. (See Tables 1, 2 and discussion section for mapping the curriculum to the U.S. Common Core State Standards.)

Online availability

As of January 2014, seventy-five percent of the stories in this curriculum are found online, and half of these are free legal downloads. A few in the other half are sold only as part of the book they were originally published in. However, as the publishing world’s true transition to digital media accelerates, the proportion of stories found individually online is expected to rise to 100 %. The current price for such downloads runs between 28 and 32 dollars or below the average cost of a high school text.

CURRICULUM

Through the lens of SF themes, the six curricular modules are now reviewed in detail with brief summaries for those teachers unfamiliar with all these works.

Introductory module

The Introductory module aims to bring SF literature to students who may encounter it for the very first time. As indicated previously, the fifteen stories are ordered so that the human interest takes precedence over any shining new technology (see the exact order in Table 1.)

The module opens with a story on extraterrestrial life, a theme that immediately signals science fiction, treated here in a thoughtfully unconventional fashion.

Extraterrestrials

- Sturgeon: “A Saucer of Loneliness.” A woman refuses to share the telepathic message from a foot-wide alien saucer, gone inert since. She is harassed to the brink of suicide by the invasion-paranoid government, to whom alien contact cannot be benign.

- Cherryh: “Chanur (excerpt.)” A ship of the lion-like Hani is moored at a trader station amidst Kif raiders. An unknown type of alien escapes its Kif abductors to seek refuge among the all-female Hani crew. The alien is recognizably male and human.

Space Faring

- Clarke: “The Star.” A Jesuit scientist’s faith in a merciful God is challenged as he brings back records of a human-like race wiped out when their star went supernova.

- Smith: “The Game of Rat and Dragon.” In this variant of space faring decidedly not based on How-the-West-Was-Won, space itself is merciless, with malevolent powers only kept at bay by the fast reflexes of telepathic cats, in what is to them is a game.

Machine Intelligence

- Zelazny: “The Engine at Heartspring’s Center.” A human-machine hybrid strikes a relationship with a woman, a fellow patient in a therapeutic center for the suicidal. Is the machine hybrid human enough to decide his own fate?

- Blish: “A Work of Art.” Richard Strauss is resuscitated to compose more classical music. In fact, his mind is ephemeral art, a form of throw-away artificial intelligence.

Devastation

- Bradbury: “There Will Be Soft Rains.” After a nuclear strike, no survivors remain. The narrated tour of the last automated house in a destroyed city is an echo of innocent lives interrupted forever, rendered in detail both absurd and poignant.

- Leiber: “Coming Attraction.” Would humans adapt to post-nuclear life as to other hardships? Surviving citizens ignore nuked boroughs, but new hooligan games and social taboos evolve around skin that may or may not show signs of irradiation

Newtopia

- Lindholm: “Cut.” A woman tries to talk her legally adult granddaughter out of ruining future sexual fulfilment for the latest body alteration fad: ritual clitoral excision.

- Spinrad: “A Thing of Beauty.” In the near future, Japan is now the top economic dog to whom dealers from the American office of antiquities sell the nation’s monumental heritage piece by piece, in a clash of distinct social rules.

Trans-human

- Keyes: “Flowers for Algernon.” A procedure makes a mentally challenged man a genius. Then the mouse on which the cure was first tested shows irreversible decline.

- Shepard: “Surrender.” A secret Central American farm has run experiments on a starving population for twenty years. Journalists now discover that politics of convenience has resulted in a great trans-human leap backward, not forward.

Inter-dimensional

- Anderson: “Brave to Be a King.” An agent of the Time Patrol that guards history from interference goes missing in Persian antiquity. His wife asks a fellow agent—who secretly loves her—to go on a rescue mission to save her husband and marriage.

- Moore: “Vintage Season.” Tourists from the future rent present-day rooms to enjoy the best Spring season in recorded history. The landlord discovers his house affords the unconcerned tourists the best seats for a pending historic catastrophe.

Wildcard

- Effinger: “Schrödinger’s Kitten.” A teenage girl lives alternate futures, one in which hesitation gets her raped and ruins her life, another where the pre-emptive murder of the rapist leads her to become a physicist working on indeterminacy.

Women Writers module

The purpose of the Women Writers module (Table 1) is to provide overall balance in writer gender.

Space Faring

- Vinge, J.: “View from a Height.” Condemned to isolation by a lack of immune system, a woman becomes a lone astronomer drifting out of the solar system forever. Now that she is twenty years out and can’t come back, science finds a cure.

- Bujold: “The Mountains of Mourning.” After interstellar travel fails for decades, a colony’s backwaters revert to subsistence and superstition. The leader’s handicapped son investigates the death of a baby girl, possibly culled for a simple cleft palate.

Machine Intelligence

- McCaffrey: “The Ship Who Sang.” A malformed baby girl is raised to control spacecraft via nerve impulses from a sealed compartment. She must now relate to a human male partner in spite of her all-machine, ship-sized interface.

- Murphy: “Recycling Strategies for the Inner City.” A woman prone to official cover-up fantasies scrounges an alien metal that assembles her other scrap into a flimsy pod.

Devastation

- Russ: “When It Changed.” After a plague kills all males of an isolated colony, the survivors rough it out, raising girls who become adults by killing a predator bare-handed in the wild. After centuries, men from Earth return to “save” the women.

- McIntyre: “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand.” In a devastated future, a healer travels a harsh desert to treat a nomadic boy with medicine derived from live snakes. Out of fear, the boy’s family threatens the very snakes that provide the boy his only chance.

Newtopia

- Le Guin: “The Dispossessed (excerpt.)” A dissident group is exiled from a world of plenty to a bleak nearby moon. Over time, scarcity influences the exiles’ behavior and even their language. Now one man’s return puts the two worldviews in stark contrast.

- Soukup: “A Defense of the Social Contracts.” A woman’s life of crime starts with an illegal wish to marry a man who has chosen legal celibacy. She refuses mild and proper treatment for her pathological condition: being desperately in love.

Trans-human

- Merril: “That Only A Mother.” The parents of a baby born after foetal exposure to radiation exhibit opposing reactions to her physical handicap and mental powers.

- Butler: “The Evening and the Morning and the Night.” A miracle cancer drug turns patients and their offspring into self-mutilating, murderous psychotics by age forty. Genetic drift saddles a rare survivor with the responsibility to help others of her kind.

Inter-dimensional

- Saxton: “The Power of Time.” A shy British tourist falls for New York City and her married Mohawk guide. Centuries in the future, a well-to-do descendant of hers acts on an unexplained pull to Manhattan, and purchases it from the Mohawk’s descendants.

- Wilhelm: “Forever Yours, Anna.” A corporate rep hires a divorcé graphologist to profile an elusive woman, using love letters to a time travel researcher annihilated in a lab explosion. The rep hopes the missing woman will lead to the man’s missing notes.

Extraterrestrials

- Dorman: “When I Was Miss Dow.” A shape-changing alien becomes a woman to better assist a visiting male scientist, and experiences the otherness of women and men.

- Goldstein: “Midnight News.” An unremarkable elderly woman, whose life sufferings include being treated poorly by others, is picked as juror by powerful aliens. She must decide if humanity will be given a chance to redeem itself, or be eradicated.

Wildcard

- Emshwiller: “Abominable.” In the style of a lay sasquatch study, a report tells of the overnight, likely voluntary disappearance of every woman on Earth. Clueless military men investigate recent sightings of women in hope of a close encounter.

Adaptations module

The Adaptations module (Table 1) leverages students’ previous exposure to film and television SF by presenting the original stories behind those adaptations for the screen, in the hope that students find the text more enriching and thought-provoking than the often simplified screenplay.

Machine Intelligence

- Aldiss: “Super-Toys Last All Summer Long.” An android programmed as a loving ersatz child realizes he is redundant, as his “mother” just won the real parent lottery.

- Bester: “Fondly Fahrenheit.” An android commits a murder he cannot remember. The owner and his android slave remain one step ahead of the law, but no matter where they flee to, the android ends up killing.

Devastation

- Ellison: “A Boy and His Dog.” In a war-ruined landscape, a young man and his telepathic dog are lured by a rare woman to a civilized underground refuge. His captors want to use him as a stud to improve the fundamentalist group’s genetic diversity.

- Tiptree: “The Screwfly Solution.” Scientists are at a loss to explain a tropical zone epidemic of otherwise sane men going berserk and killing women, own wives and daughters included, as if exterminating them made perfect sense.

Newtopia

- Sheckley: “The Prize of Peril.” A TV contestant will win a fortune if he lasts one week against professional killers. Tips from the audience, for or against the outmatched target, are an integral part of game play.

- Silverberg: “To See the Invisible Man.” Social isolation is used to dissuade crime. Anyone who interacts in the least with the clearly marked guilty is condemned in turn.

Trans-human

- Farmer: “Day of the Great Shout.” A dead 19th Century explorer wakes up resurrected in an untamed landscape, along with others from all over Earth’s history.

- Herbert: “Dune (excerpt.)” Over millennia, humans develop mental abilities: fold space between the stars, control others, perform complex computations. These powers stem from a spice whose single planet source just changed hands between feuding houses.

Inter-dimensional

- Kuttner & Moore: “Mimsy Were the Borogoves.” Children find sophisticated toys from the future which allow their minds to interact with other dimensions of space. Parents are unaware of the risks posed by their children’s use of these adaptive toys.

- Dick: “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” An unremarkable man wishing to play secret agent on Mars purchases realistic false memories. However, the treatment reveals he is, in fact, a real agent whose memory of a real mission was expertly blocked.

Extraterrestrials

- Van Vogt: “Black Destroyer.” While exploring ruins on a distant planet, a human crew allows an alien onboard, who promptly picks them off one by one. (The “Alien” film-makers settled with the story’s uncredited author—see Jameson, 2005, p. 325.)

- Henderson: “Pottage.” A teacher assigned to a remote village discovers her pupils are stranded aliens, forbidden to use telekinetic powers that may expose them. She leads them to embrace their nature and powers, but an accident critically injures a child.

Space Faring

- Simak: “Beachhead.” A heavily armed military party is tasked to establish a beachhead for future colonization. The primitive natives warn that coming to the planet is a grave mistake, and that the earthmen will never go home again.

- Godwin: “The Cold Equations.” A colony will be wiped out unless a scout ship delivers a vaccine. Unaware of the stakes, a teenager stows away to see her brother, and her extra mass makes the colony unreachable. Regulations require the pilot to space her.

Wildcard

- Gibson: “Johnny Mnemonic.” A data trafficker moves information on surgically implanted memory modules, inaccessible except to the corporate buyer’s machine interface. The data is stolen from the Asian mafia, whose assassin tracks the runner.

Classic module

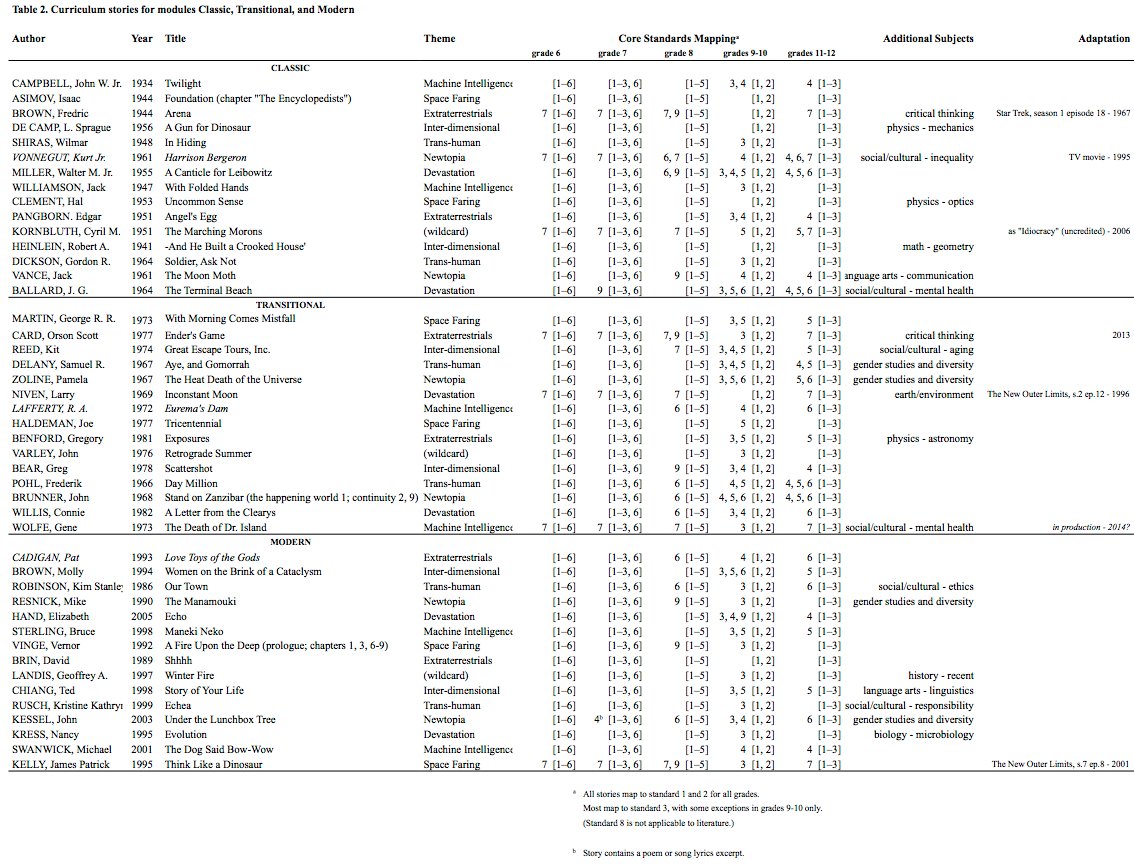

The goal for the Classic module (see Table 2) is to give a sense of the development of SF up to the mid-sixties, using stories that nevertheless continue to resonate with modern readers.

Machine Intelligence

- Campbell: “Twilight.” A man returns from the distant future to describe a humanity so well served by its machines that it has lost all purpose.

- Williamson: “With Folded Hands.” Citizens discover that their androids are prepared to carry the prime directive to protect their masters to unforeseen and quite logical extremes.

Space Faring

- Asimov: “Foundation” (excerpt.) At the edge of the decadent human galactic empire, the nominal leaders of a city-sized colony of imperial librarians are oblivious to the impending revolt of neighboring provinces, who have the colony in their sights.

- Clement: “Uncommon Sense.” A collector of alien plants and animals must use his wits to regain access to his ship and wrest control of it from his two mutineer hired hands, who intend to maroon him on the planet as soon as repairs are finished.

Extraterrestrials

- Brown, F.: “Arena.” A human scout is whisked away from interstellar war. The powerful beings who abducted him announce that how he fares bare-handed in a contest to the death against a single alien enemy will decide the fate of both species.

- Pangborn: “Angel’s Egg.” After a flurry of countryside flying saucer activity, a retired biologist finds an egg from which emerges a six-inch tall, winged female who soon develops a telepathic relationship with him.

Inter-dimensional

- De Camp: “A Gun for Dinosaur.” Too lightweight to use the requisite heavy caliber gun, a well-intentioned man still goes on a time-travel dinosaur safari.

- Heinlein: “’–And He Built a Crooked House’.” An architect builds a house of cubic rooms stacked to represent a four-dimensional cube “unfolded” in our three normal dimensions. Then, an earthquake collapses the eight cubes into one, a real hypercube.

Trans-human

- Shiras: “In Hiding.” A psychiatrist finds that the thirteen year-old who cautiously opens up to him has fooled all the tests in order to mask his superhuman intelligence.

- Dickson: “Soldier, Ask Not.” Planetary colonies have become much specialized, and one supplies naturally skilled soldiers to help others fight wars. An ex-mercenary is caught in an intrigue that impacts the nature and future of the human race.

Newtopia

- Vonnegut: “Harrison Bergeron.” To ensure perfect equality for all, the state subjects anyone with above average gifts to incapacitating and debilitating distractions.

- Vance: “The Moon Moth.” In a society where playing a slew of portable musical instruments according to circumstance is the key to successful interaction, a musically unskilled diplomatic attaché must stop a compatriot who is an assassin.

Devastation

- Miller: “A Canticle for Leibowitz.” In a post-nuclear devastated world, monks seek to preserve every scrap of knowledge. A novice has trouble convincing his abbot that the ancient find he made is genuine and significant.

- Ballard: “The Terminal Beach.” Having lost his entire family, a man goes to the abandoned Pacific island test site of the first hydrogen bomb, in order to make sense of a modern world where stockpiles of thousands of nuclear weapons are acceptable.

Wildcard

- Kornbluth: “The Marching Morons.” A man wakes up in a future world populated by dimwits and kept running by desperate efforts from the few bright people. Unencumbered by any such desire to serve, the man finds opportunities galore.

Transitional module

The objective of the Transitional module (Table 2) is to present exemplars from the middle of the story of science fiction, when some writers aimed to make the genre more literary, amidst others who pushed to keep the science in science fiction.

Space Faring

- Martin: “With Morning Comes Mistfall.” At a planet’s mountain resort, a journalist covers the work of scientists tasked to prove or disprove the existence of the mythical wraiths said to claim lives every year, as they come and go with the thick daily mists.

- Haldeman: “Tricentennial.” A malfunctioning starship engine threatens the crew with a relativistic time dilation that will forever maroon them into the far future.

Extraterrestrials

- Card: “Ender’s Game.” Because he represents humanity’s best chance against ruthless insect-like aliens encountered in deep space, a promising boy is recruited to an orbiting station boot camp to train in strategic war games.

- Benford: “Exposures.” Database records lead a contemporary astronomer to discover a radiation threat headed our way from the galactic core. Except the observations cannot possibly have been made from Earth.

Inter-dimensional

- Reed: “Great Escape Tours, Inc.” Senior citizens find a portal to another dimension and a fountain of youth, one that does not operate quite the way they expected.

- Bear: “Scattershot.” After a weapon scatters sections of a space battleship into different alternate universes, the sole survivor from this universe must deal with the surviving crew from other sections, some of whom are as alien to her as she to them.

Trans-human

- Delany: “Aye, and Gomorrah.” Members of a corps of youngsters neutered so they can better stand the harsh radiation of space come down to Earth for a raucous shore leave. This includes encounters with people sexually attracted to the neutered.

- Pohl: “Day Million.” One million days from now, “boy meets girl” covers an array of unexpected behavior and physical details, as transformed humans fall in love.

Newtopia

- Zoline: “The Heat Death of the Universe.” Overwhelmed by the minutiae of her life as a young housewife and mother, a woman finds a parallel between thermodynamics’ notion of rising entropy and the increasing disorder in her own constrained universe.

- Brunner: “Stand on Zanzibar” (excerpt.) The dysfunctional and overpopulated world of tomorrow becomes a tapestry of over-stimulation and media saturation.

Devastation

- Niven: “Inconstant Moon.” When the evening moon becomes much brighter in a matter of minutes, a writer realizes something has happened to the sun on the other side of the Earth. The world will end in devastation with the next sunrise.

- Willis: “A Letter from the Clearys.” A family is saved from nuclear holocaust by their absence from the city. Willing and able to adapt to life as a survivor, the teenage daughter finds the adults’ attention is consumed by a way of life they have lost forever.

Machine Intelligence

- Lafferty: “Eurema’s Dam.” Because he thinks of himself as not so bright, a man invents machines to accomplish increasingly sophisticated tasks in his place.

- Wolfe: “The Death of Dr. Island.” In an artificial tropical island environment run by a psychiatrist computer, a teenage boy deals with his own shortcomings and those of the other two patients, a confused young woman and a homicidal man.

Wildcard

- Varley: “Retrograde Summer.” Forced to live in space-limited domed warrens on other planets, humanity enforces a strict rule of One Person, One Child. On Mercury, a young man greets his clone sister from the Moon. Mom will have to explain.

Modern module

The purpose of the Modern module (Table 2) is to complete the picture of the evolving SF genre up to the first decade of the new century.

Extraterrestrials

- Cadigan: “Love Toys of the Gods.” A UFO abductee, who claims to have been forced to have sex with aliens, meets with other abductees, and learns that indeed the truth is out there.

- Brin: “Sshhh...” The Earth president devises an unusual ploy to ensure humanity deals smoothly with the first peaceful, far advanced aliens to arrive from the stars.

Inter-dimensional

- Brown, M.: “Women on the Brink of a Cataclysm.” An established sculptor jumps to parallel universes where her life turned out very differently, chased by alternate versions of herself who either want to take over her life and success, or save their own.

- Chiang: “Story of Your Life.” While working on deciphering the language of recently contacted aliens, a linguist begins to experience the passage of time in a non-linear fashion, a possibility hinted at by the alien language structure.

Trans-human

- Robinson: “Our Town.” In posh cities isolated from the rest of the primitive world, sculptors install purposely-grown human clones into locked postures and frozen expressions. At an exhibit, a maverick sculptor breaks all rules by releasing the clones.

- Rusch: “Echea.” A young refugee has never received the mechanical brain implants that would allow her to fully participate in society. If her adoptive mother provides such, it will wipe out the personality the mother bonded with in the first place.

Newtopia

- Resnick: “The Manamouki.” A space habitat reconstitutes the simpler, ideal life of the Kikuyu African tribe prior to European colonization. A westernized African couple emigrates there, but the enthusiastic wife fails to leave all of her former values behind.

- Kessel: “Under the Lunchbox Tree.” In a strict matriarchal colony on the Moon, a rebelling teenage girl involves a lowly male driver in her escapade.

Devastation

- Hand: “Echo.” On a Maine coastal island, accompanied only by her wolfhound, a self-sufficient woman gradually loses her infrequent wireless online contact with a former lover from the slowly crumbling outside world.

- Kress: “Evolution.” A nation-wide epidemic erodes a town’s social order. To find her runaway teen, a blue-collar woman contacts the father, who dumped her after her teenage pregnancy. As an added complication, the woman received hard time for exacting an earlier revenge on the father.

Machine Intelligence

- Sterling: “Maneki Neko.” Web-based artificial intelligences prompt people to give strangers unsolicited, specific, timely gifts. The giver gets favors in return, so no one questions the motives of the artificial personalities when the gift’s purpose is obscure.

- Swanwick: “The Dog Said Bow-Wow.” In a future Earth once ravaged by networked artificial intelligences, a pair of con artists attempt to infiltrate Buckingham Palace using a broken modem, a rare relic from the lost era of the machines.

Space Faring

- Vinge, V.: “A Fire Upon the Deep” (excerpt.) Humans archaeologists tinker with an ancient data archive on a long dead world, and unwittingly unleash a malevolent power that threatens all sentient races in galactic civilization.

- Kelly: “Think Like a Dinosaur.” Cold-blooded aliens let humans use a teleportation device that transmits only their information into a new body at the destination star. The catch is that the traveller’s original body must be destroyed.

Wildcard

- Landis: “Winter Fire.” In a near-future Salzburg, a girl tries to survive horrific conditions as warring factions gradually destroy the city, killing the inhabitants. Meanwhile, nations of the world cancel each other’s influence and do nothing.

DISCUSSION

Advantages of a theme based curriculum

As seen in the above summaries, the use of SF themes to characterize a text bridges the gap between a story’s thrust and broad human interests. Thus, theme is a natural means to bring students to SF, a worthwhile endeavor as the human condition is illuminated by SF in ways impossible to achieve otherwise. This best result from the genre’s uniqueness is exemplified by stories such as Effinger’s “Schrödinger’ Kitten,” Russ’ “When It Changed,” and Dick’s “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.”

Themes in SF literature also compensate for the superficial adoption of SF tropes in other media. In June 2013, BBC America announced the documentary series “My God, It’s Full of Stars: A Journey to the Edge of Science Fiction” (BBC Worldwide Media Centre, 2013), slated for December of the same year. Its intent to tell the story of SF “through its impact on cinema, television and literature,” in that order, suggests literature will take an immediate back seat to the screen. In addition, the themes the series will focus on, “time travel; the exploration of space; robots and artificial intelligence; and aliens” suggests that other themes will be ignored such as Devastation (On the Beach, Dr. Strangelove, 12 Monkeys); Newtopia (Metropolis, Brazil, The Handmaid’s Tale); and Trans-human (2001: A Space Odyssey, Dune, Gattaca.) Given such biases, the use literature to represent all of SF’s corpus seems an appropriate counter.

The thematic categories used here can be traced back through all of history, and the relevance of SF is easily communicated by using the keywords on which the relevant changes hinge:

Science fiction is about the consequences of change in the tools we use, the settings we explore, others we meet, the invisible dimensions we think about, our essence as humans beings, the rules by which we organize societies, and the habitat we transform.

This last sentence becomes a de facto operational description of SF. Teachers may find this more useful than a formal definition of the genre, fraught with pitfalls (e. g. Rabkin, 2008) and thus prone to invite attention to exceptions rather than the rule.

Comparison to existing curriculum anthologies

The two best known anthologies aimed at SF literature curricula are the single editor, four-volume “The Road to Science Fiction” (Gunn, 2002) and the six-editor, single volume “The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction” (Evans et al., 2010.)

The first was published in paperback format between 1977 and 1982 as a story-based teaching tool, and later updated as textbooks. Stories are selected for their idea’s first appearance, but Gunn introduces them in-text for the author’s place in the history of SF, not for the change brought about by the idea. This strength in the historical element leaves no room for a discussion of theme, making the series less relevant for new readers.

The second presents the stories in chronological order, then annexes a table of contents re-sorted according to nine undocumented themes. The absence from the list of the colonization of space, one of SF’s basic myths (Williamson & Gunn, 1975,) is a surprise. Another is a Gender and Sexuality theme, as it relates to literary criticism such as Postcolonial, Marxist, or Feminist theory (see James and Mendlesohn, 2003; Bould et al., 2009), all of considerable interest, but none a distinguishing feature of SF.

Mapping to Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts

The Common Core State Standards Initiative (2012) www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy set U.S. school curriculum requirements for proficiency in English Language Arts for pre-college levels. From grade 6 to grade 12, the Reading category has nine metrics grouped into four classes: Key Ideas and Details, Craft and Structure, Integration of Knowledge and Ideas, and Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity. Each metric is defined for every grade level, becoming more complex as a student advances through each grade, and five of the nine metrics relate to theme directly.

Metric one, about “what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text,” asks of students to provide increasingly thorough textual evidence to support their view. Metric two states “Determine the theme or central idea of a text,” adding for grade 6 “… and how it is conveyed through particular details,” whereas for grade 9-10 “… and analyse in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details.” Metric five relates to how the structure of a text helps convey its meaning. Theme is also addressed indirectly by metric seven, on the interaction of literature with other media, and directly by metric nine, on the treatment of similar themes or topics in different fictional and non-fictional genres.

In other words, theme maps readily to educational core standards, more so than other candidate descriptors, be it literary criticism (structuralist, postmodern, marxist, feminist, and so on), genre history (Verne and Wells novels, rise of specialty magazines and editors, appearance of book imprints, etc.), or SF subgenre (space opera, new wave, cyberpunk, slipstream, and so forth.)

Hartwell (1996) argues that, contrary to popular opinion, the presence of the word “science” does not make science fiction difficult to understand, since “twelve-year-olds who read it understand it perfectly” (p.14.) He finds SF to be so pervasive in U.S. contemporary culture that children are exposed early to its basic concepts, via comic books or TV or film, so that “sometimes, usually by the age of twelve, a kid progresses to reading science fiction in paperbacks, in magazines, book club editions—wherever he [or she] can find it, because written SF offers more concentrated excitement.” (p. 20.)

In other words, juvenile readers will seek SF aimed at a general audience and experience no particular difficulty with it. Whether this is because publishers consciously keep the teenage reader in mind when they market SF is irrelevant. Teachers will find the stories in the present curriculum suitable for readers from grade 6 onwards, with minor exceptions due to local cultural custom.

The grade 6-12 core standards are mapped to the individual stories in the proposed curriculum in Tables 1 and 2.

Usage beyond the teaching of English literature

Modularity goes beyond the teaching of English literature. Although designed for different reasons, the Women writers and Adaptations modules may be used to introduce SF in courses on Women and Film Studies respectively. Furthermore, as seen in the Additional Subjects column of Tables 1 and 2, the curricular interest of the stories is not limited to those three topics. It includes the hard sciences (astronomy, physics, astronomy, mathematics, biology), soft sciences (psychology, sociology, linguistics), humanities (history, philosophy, theology) and topics in-between (computer science, critical thinking.)

The assignment of a theme to a story is less a definitive choice than a useful way to relate it to larger contexts. Alternative interpretations as to which theme best represents a story provide a basis for classroom discussion. Such debate furthers the understanding of the purpose of SF: to explore the consequences of introducing new ideas in an ever-changing world.

Advantages of a virtual anthology

Education is moving away from the printed textbook model and towards the downloadable e-book for three reasons: adaptability, ease of distribution, and cost (see for instance Schwartz, 2012). www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2012/mar/15/ebooks-academic-future-universities-steven-schwartz

However, what to date is missing in SF studies is a teacher-approved list of standards-mapped, accessible short stories.

This curriculum provides teachers with the flexibility to tailor an anthology to their needs, using an external source as a guide. This curriculum structures stories in modules that are easily recombined or subdivided. Whether the purpose is to teach SF literature at the high school or university level, in a course dedicated to SF or on genre literature, and with the emphasis on reading a great number of texts or delving deeper into a select few, a modular online curriculum is ideally suited to multiple needs.

In addition, an affordable number of SF stories can supplement courses with a textbook already assigned. These courses need not be offered by the same department, or even belong to the same academic discipline. Should the need arise for SF curricula dedicated to other disciplines, the present curriculum provides a base from which to expand. Best of all, a virtual anthology encourages students to read, regardless of the academic context in which SF literature is presented, because ownership of mobile devices such as digital tablets and cell phones rises steadily (Brenner, 2013), and readers increasingly use portable devices to do their reading (Rainie & Duggan, 2012.)

CONCLUSION

This paper has shown how a theme-based, modular, online curriculum can be used to introduce science fiction literature to new readers. Theme emphasizes the relevance of SF to the human condition. The modularity combined with the online purchase of individual stories provides the flexibility to: teach SF at all educational levels from middle grade upwards, tailor the amount of material to the reading needs of a particular group, and even use it in courses other than English literature.

Alvin Toffler coined the term “future shock” to describe the reaction to the premature arrival of the future, to having too many changes come in too short a time. One of the safeguards proposed by Toffler (1970) is to read science fiction:

Our children should be studying Arthur C. Clarke, William Tenn, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury and Robert Sheckley, not because these writers can tell them about rocket ships and time machines but, more important, because they can lead young minds through an imaginative exploration of the jungle of political, social, psychological and ethical issues that will confront these children as adults. (p. 425)

The best reason to teach SF in schools goes far beyond the early development of a taste for science and mathematics. Science fiction empowers students to think about and deal with the consequences of change, in a real world that keeps changing ever faster.

Acknowledgements: This work would not have been possible without Dr. K. Kitts, whose generous help and guidance is gratefully acknowledged.

About Jean Asselin

Leave A Comment